A Nova Scotia high school student is asserting she was reduced to “second-class citizenship” after her Halifax aikido school followed provincial human rights law and accommodated a male student’s religious request not to touch his female classmates.

“I felt degraded, discriminated against, I felt like a woman in the 1950s,” said Sonja Power, 17, a former student at Halifax’s East Coast Yoshinkan Aikido, a school operated out of the city’s Lakeside Community Centre. “We wouldn’t allow someone using their religion to discriminate against someone’s race, so why would they use it to discriminate against somebody’s gender?”

Ms. Power, a resident of the Halifax suburb of Upper Tantallon, NS, had been a student at East Coast Yoshinkan since the age of six.

In the spring of 2012, Ms. Power, then 15, was just on the verge of earning her aikido black belt when she said a man enrolled at the school and told its owner that, for reasons of his Islamic faith, he was not allowed physical contact with women.

The request would not have been noticed in a pottery class or a fencing course, but Aikido — like any martial art — is uniquely physical. The ultimate effect, said Ms. Power, was that sessions were suddenly being divvied up by sex.

The school’s sensei (teacher), “would put all the women on one side and then offer a side for the Muslim man so there wouldn’t be any problems,” she said.

And when it came time for the customary end-of-class handshakes, “he would shake hands with all the other men in the dojo, but he wouldn’t even come over and look at the women … he just ignored us,” said Ms. Power.

The man also refused to bow, apparently telling the dojo’s sensei that he only bowed to Allah. Bowing is a big part of the Japanese martial art, and aikido students are expected to regularly bow to classmates, the sensei and the front wall of the dojo, which is traditionally adorned with portraits of aikido’s pioneers.

‘I felt like a woman in the 1950s’

Along with her mother, Ms. Power said she approached the sensei with her concerns about the new environment, but was told that it was the student’s religious right. “[The sensei] told us to get used to it,” said Michele Walsh, Ms. Power’ mother.

Aiming to complete her training, Ms. Power nevertheless stayed in the school for another five months, but said her breaking point came when the male student began distributing religious literature.

In July of 2012, said Ms. Power, the student handed out copies of Islam; From darkness to light a booklet written by Toronto-based Islamic author Suhail Kapoor.

Several passages stuck out for the 15-year-old. “[When] a woman chooses to show her body in one form or another, the message is only one: she wants attention and possibly much more,” it reads. The booklet also authorizes husbands to administer a “light strike” to their wives in cases of “serious moral misconduct.”

“I couldn’t go to the same dojo with someone who thinks that way,” said Ms. Power.

“I thought why would someone’s religion — something that they choose to follow — trump my gender, which is something that I was born with?”

Steve Nickerson, a fifth degree black belt and the owner and sensei of East Coast Yoshinkan Aikido, wrote in an email to the National Post that although he met the student’s request to avoid physical contact with women, the student “interacted, without physical contact, with women in my classes each week as part of our regular program.”

As for the bowing, Mr. Nickerson said the request was made respectfully and was “very easy to accommodate.”

“I believe every person should have an equal opportunity to participate in recreational activities and I would not deny this student access to my classes,” he wrote, noting that he made the accommodation with the confidence that it would not be “disadvantaging any other person’s participation in my classes.”

The decision, he said, was supported by both the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission and the Halifax Recreation Administration, which operates Lakeside Community Centre.

Both informed him that the steps he took were “prudent, lawful and correct,” wrote Mr. Nickerson.

Lisa Teryl, a lawyer for the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission, was unable to comment on the aikido case specifically, but acknowledged the stickiness of weighing the “competing rights” of gender equity versus religious beliefs.

“In the fabric of Canadian society, [gender segregation] isn’t something that, in a secular sense, we support … we generally see it as a bad thing,” she said.

‘Why would someone’s religion — something that they choose to follow — trump my gender, which is something that I was born with?

At the same time, she said, the law requires reasonable accommodation of religious views, which are generally given much higher consideration than mere matters of personal preference.

“If it doesn’t cost us to the point of undue hardship, then we need to try to … support them, and not have them feel persecuted for their deeply-held belief,” she said.

The Halifax Regional Municipality, operators of Lakeside Community Centre, similarly acknowledged a tricky gray area in cases of competing rights.

“[Sometimes] the exercise of human rights by some individuals can come into conflict with human rights entitlements of others,” wrote Halifax recreational coordinator Peter Jollimore to the National Post, adding that “often, such conflicts can be resolved by simple dialogue between the affected parties.”

Amir Hussain is a theology professor at Los Angeles’ Loyola Marymount University and wrote his thesis on Toronto Muslim communities.

Speaking to the National Post, he called the student’s requests an unusual interpretation of mainstream North American Islam, but said “it could well be that this person feels that this is what their religion is demanding.”

Said Mr. Hussain, “in Islam, you’re supposed to respect your teachers. You’re not supposed to bow down to other gods, but the sensei isn’t your god.”

http://news.nationalpost.com/2014/01/14/teen-felt-degraded-after-teacher-divided-aikido-classes-by-gender-following-male-students-religious-request/

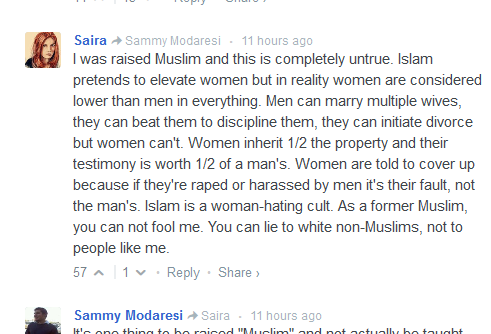

Best comment of that article:

“I felt degraded, discriminated against, I felt like a woman in the 1950s,” said Sonja Power, 17, a former student at Halifax’s East Coast Yoshinkan Aikido, a school operated out of the city’s Lakeside Community Centre. “We wouldn’t allow someone using their religion to discriminate against someone’s race, so why would they use it to discriminate against somebody’s gender?”

Ms. Power, a resident of the Halifax suburb of Upper Tantallon, NS, had been a student at East Coast Yoshinkan since the age of six.

In the spring of 2012, Ms. Power, then 15, was just on the verge of earning her aikido black belt when she said a man enrolled at the school and told its owner that, for reasons of his Islamic faith, he was not allowed physical contact with women.

The request would not have been noticed in a pottery class or a fencing course, but Aikido — like any martial art — is uniquely physical. The ultimate effect, said Ms. Power, was that sessions were suddenly being divvied up by sex.

The school’s sensei (teacher), “would put all the women on one side and then offer a side for the Muslim man so there wouldn’t be any problems,” she said.

And when it came time for the customary end-of-class handshakes, “he would shake hands with all the other men in the dojo, but he wouldn’t even come over and look at the women … he just ignored us,” said Ms. Power.

The man also refused to bow, apparently telling the dojo’s sensei that he only bowed to Allah. Bowing is a big part of the Japanese martial art, and aikido students are expected to regularly bow to classmates, the sensei and the front wall of the dojo, which is traditionally adorned with portraits of aikido’s pioneers.

‘I felt like a woman in the 1950s’

Along with her mother, Ms. Power said she approached the sensei with her concerns about the new environment, but was told that it was the student’s religious right. “[The sensei] told us to get used to it,” said Michele Walsh, Ms. Power’ mother.

Aiming to complete her training, Ms. Power nevertheless stayed in the school for another five months, but said her breaking point came when the male student began distributing religious literature.

In July of 2012, said Ms. Power, the student handed out copies of Islam; From darkness to light a booklet written by Toronto-based Islamic author Suhail Kapoor.

Several passages stuck out for the 15-year-old. “[When] a woman chooses to show her body in one form or another, the message is only one: she wants attention and possibly much more,” it reads. The booklet also authorizes husbands to administer a “light strike” to their wives in cases of “serious moral misconduct.”

“I couldn’t go to the same dojo with someone who thinks that way,” said Ms. Power.

“I thought why would someone’s religion — something that they choose to follow — trump my gender, which is something that I was born with?”

Steve Nickerson, a fifth degree black belt and the owner and sensei of East Coast Yoshinkan Aikido, wrote in an email to the National Post that although he met the student’s request to avoid physical contact with women, the student “interacted, without physical contact, with women in my classes each week as part of our regular program.”

As for the bowing, Mr. Nickerson said the request was made respectfully and was “very easy to accommodate.”

“I believe every person should have an equal opportunity to participate in recreational activities and I would not deny this student access to my classes,” he wrote, noting that he made the accommodation with the confidence that it would not be “disadvantaging any other person’s participation in my classes.”

The decision, he said, was supported by both the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission and the Halifax Recreation Administration, which operates Lakeside Community Centre.

Both informed him that the steps he took were “prudent, lawful and correct,” wrote Mr. Nickerson.

Lisa Teryl, a lawyer for the Nova Scotia Human Rights Commission, was unable to comment on the aikido case specifically, but acknowledged the stickiness of weighing the “competing rights” of gender equity versus religious beliefs.

“In the fabric of Canadian society, [gender segregation] isn’t something that, in a secular sense, we support … we generally see it as a bad thing,” she said.

‘Why would someone’s religion — something that they choose to follow — trump my gender, which is something that I was born with?

At the same time, she said, the law requires reasonable accommodation of religious views, which are generally given much higher consideration than mere matters of personal preference.

“If it doesn’t cost us to the point of undue hardship, then we need to try to … support them, and not have them feel persecuted for their deeply-held belief,” she said.

The Halifax Regional Municipality, operators of Lakeside Community Centre, similarly acknowledged a tricky gray area in cases of competing rights.

“[Sometimes] the exercise of human rights by some individuals can come into conflict with human rights entitlements of others,” wrote Halifax recreational coordinator Peter Jollimore to the National Post, adding that “often, such conflicts can be resolved by simple dialogue between the affected parties.”

Amir Hussain is a theology professor at Los Angeles’ Loyola Marymount University and wrote his thesis on Toronto Muslim communities.

Speaking to the National Post, he called the student’s requests an unusual interpretation of mainstream North American Islam, but said “it could well be that this person feels that this is what their religion is demanding.”

Said Mr. Hussain, “in Islam, you’re supposed to respect your teachers. You’re not supposed to bow down to other gods, but the sensei isn’t your god.”

http://news.nationalpost.com/2014/01/14/teen-felt-degraded-after-teacher-divided-aikido-classes-by-gender-following-male-students-religious-request/

Best comment of that article:

0 comments:

Post a Comment